Getting Rid Of Cars…A La Bogota

Community Care – Individuals Controlling Their Own Support?

March 30, 2008A Register To Match Needs With Grey Nomad Skills?

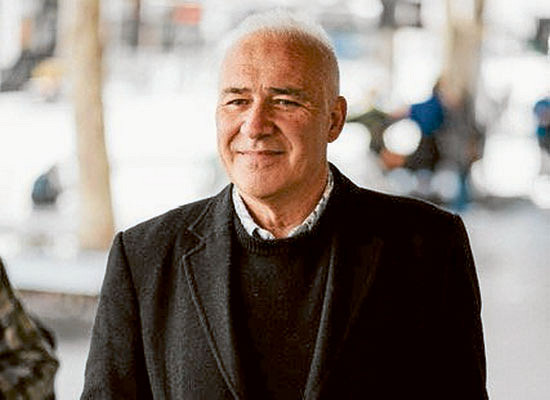

April 3, 2008From 1998 – 2000 Enrique Peñalosa was Mayor of Bogotá, Columbia, a city that ‘many had given up on’ such were the slums, chaos, violence, and traffic. He says he led ‘the transformation of a city’s attitude from one of negativist hopelessness to one of pride and hope’.

He did it all, in part, by declaring a war on private cars.

An Amazing Three-Year Term As Mayor Of Bogota

As the new mayor Enrique announced that a city can be friendly to people or it can be friendly to cars, but it can’t be both. He shelved highway plans and poured the billions saved into parks, schools, libraries, bike routes and the world’s longest ‘pedestrian freeway’.

Clearly law-abiding places like Denmark and Sweden are an inspiration, but sometimes the solutions to problems are not obvious. We think traffic jams can be solved by building more roads, but:

“This has never worked, anywhere in the world. Building more roads will just lead to more traffic jams…If we define our value by income alone, we are condemning ourselves to be losers for the next 500 years…happiness is what it should be all about.”

He explained the philosophy behind the war on cars and Bogota’s transformation, during the plenary lecture at the 2006 World Urban Forum in Vancouver, beginning with a sobering reminder to the mayors of developing world cities:

“If you base progress on per capita income, then the developing world will not catch up with rich countries for the next three or four hundred years. The difference between our incomes is growing all the time. So we can’t define our progress in terms of income, because that will guarantee our failure. We need to find another measure of success.”

His answer is ‘Happiness’ but WHAT makes us happy?

“We need to walk, just as birds need to fly. We need to be around other people. We need beauty. We need contact with nature. And most of all, we need not to be excluded. We need to feel some sort of equality.”

The problem in Bogota was that most people didn’t have access to the public space that is supposed to make such happy things happen. The wealthy had turned city footpaths into parking lots for cars. Public parks had been fenced off, essentially privatised by neighbours with the government spending little of its budgets on highways and road improvements.

So while the wealthy in Bogota could spend their weekends in country clubs or private gardens, the poor had little but jammed streets and televisions to occupy their leisure time. Balance was needed.

“Bogota has demonstrated that it is possible to make dramatic change to how we move around our cities in a very short timeframe…It’s simply a matter of choosing to do so. We could improve our air quality and dramatically reduce our emissions anytime we want. It’s easy to do. For example, we can improve the capacity of our existing bus system without adding a single bus. All it would take is a can of paint, and you’d have dedicated bus lanes. It doesn’t require huge amounts of money. It simply requires a choice.”

How Did It All Happen?

The official War on Cars began when the footpaths were cleared of cars.

After the first wildly popular ‘Car-Free Day’ in 2000, residents voted in a referendum to make the event an annual affair. The city was transformed from a place of hopelessness to one of civic pride.

- A system that banned 40 percent of vehicles from the roads during rush hour was launched

- the city council convinced it could raise the tax on petrol

- half the revenue was used to fund a rapid bus system

- prime space on the city’s main arteries was handed over to this bus system that now serves more than 500,000 citizens

- petrol taxes were increased

- car owners prohibited from driving during rush hour more than three times per week

- by shifting the budget away from private cars school enrolment was boosted by 30 per cent, 1,200 parks built, the core of the city revitalised and running water to hundreds of thousands of poor

In Australia

In an ABC interview with David Mark, discussing how to address traffic congestion in Sydney, Brisbane and Melbourne, Enrique said:

“I think one thing that has to be avoided is to build more highways, because they stimulate people going farther and farther away. So if we want to stimulate density, there are two things that must be done.

First, no more highways. Second, you have to put public transport on the highways that you do have.

So this is one thing that I think could be improved, to have more bikeways, and I do believe that with a bus system that is to be given total priority in road use, you could really solve basically most of your transport problems.

Any great city has to restrict motorcar use, but one thing that is clear is that people will not give up their cars voluntarily. I mean, this is a matter of political decision. These are not engineering decisions.

A good city is not the result of many selfish individual decisions. First you have to have a vision of what is it that you want, a collective vision. And then you have to restrict many individual behaviours.

There clearly is a conflict between a city for cars and a quality city for people. This is something that has to be realised fully. You cannot have both.”

Peñalosa A Fan Of Traffic

“Traffic is a sign that you have enough density to support transit an it is one of the best ways to get people out of their cars. Anywhere you look in the world, when people use public transport, it’s not because of some high level of consciousness. It’s because private driving is restricted. What is the easiest way to restrict private cars? Traffic. Just look at New York.

Transport is the only urban problem that actually gets worse as you get richer, and it’s only solved by changes in our behaviour. And this is always a political issue.”

Bogota’s story proves that change is not so much a matter of spending big money as it is a matter of choice.

Enrique Penalosa was a recent guest at the EcoEDGE 2 Conference in Melbourne, where the world’s leading sustainability experts in tackled the economic, aesthetic and ethical dimensions in making sustainable cities. Let’s hope he made an impression in the right quarters!