Lower Supermarket Prices Through Less Regulation In 2013?

Affordable Housing For Women Wins Award

January 25, 2013A Travel And House-Sitting Companion?

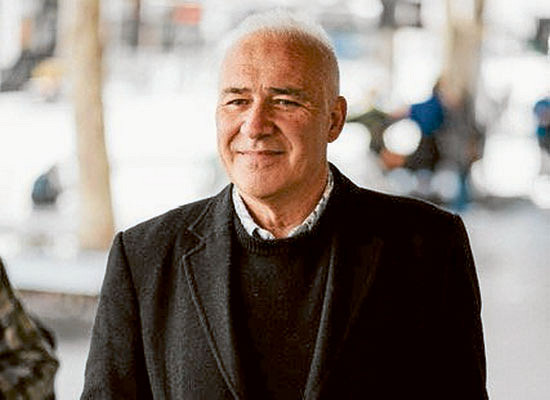

January 30, 2013To drive down supermarket prices we need more supermarkets, not more regulation says Tim Wilson, co-author of ‘Consumer-first supermarket reform’, available here.

The Typical Australian Experience

Tim says the typical Australian experience, in most suburbs, is:

“Consumers are price sensitive and pay 10-20 per cent of their total income on food. To keep costs down, they buy their private-labelled groceries at Aldi, Coles, Woolworths or a Supa IGA. They scan home-delivered catalogues and listen and watch radio and television promotions to see where the best deal is this week.

But everyone runs out of milk at 9pm and pays a higher price at their local store for convenience.

In that context it’s hardly surprising Australians are some of the least loyal supermarket customers in the world. Nearly 60 per cent of us are likely to change supermarkets for a mere 5 per cent discount.”

We’ve Been Trained To Be Disloyal

Apparently we’ve been ‘trained’ to be disloyal, the reason why we are deluged with catalogues to lure us in. As disloyal customers, Tim says, the most important thing is to be offered choice.

Market Share?

In 2008 the ACCC estimated that the two major supermarkets control between 55 per cent and 60 per cent of the market and this is likely to be lower now with Aldi and Costco on the scene.

“Analysing packaged groceries also only provides one measure of competition. Coles and Woolworths’ dominance drops in fruit and vegetables, meat and poultry and bread and cakes because people like their local fruit shop, butchers and bakeries, which are often located in the same mall.”

The Recommendation In 2013

Despite the fact that Rod Sims, in line to head up the ACCC, has stated that 2013 will be ‘the year of supermarket regulation to make the sector more competitive’ Tim says:

“The ACCC should be advocating for the end of local and state regulations that make it more expensive for new supermarket entrants.

The consequences are backed up by a 2007 federal government study that concluded that the absence of a major supermarket in a community reduced competitive pressure, leading to prices 17 per cent higher than in those communities that did have a major supermarket.

If that cost was passed on, households in those communities that lack a major supermarket, particularly in new and outer suburbs and rural and regional communities, would pay an extra $1800 a year.”

Tim is adamant that the only way to keep food prices down is by improving competition by removing barriers to entry.

We’ll see what happens